The Norton and Nancy Dodge Collection of Nonconformist Art from the Soviet Union, donated to the Zimmerli in 1991, underwent an extensive reinstallation in spring 2012. Museum staff took the opportunity to rotate works on display, as well as compose more in-depth translations from Russian to English of some of the key artists’ texts and interpretations to create a more comprehensive cultural context for visitors.

The refurbishment continues the Zimmerli’s commitment to preserving the artworks in its trust, one of the cornerstones of the museum’s strategic plan, and presenting these groundbreaking artworks that document a key period in the twentieth century.

“The prospect of seeing more parts of the Dodge Collection, as the Zimmerli periodically reinstalls the two floors of these generous galleries, ought to excite anyone interesting in appreciating the meaningful ways in which history and art can clash,” wrote Tom L. Freudenheim in a May, 2012, article in the Wall Street Journal. “If we really want to come to terms with a fuller range of modernisms, a trip to the Rutgers campus is now required.”

Norton and Nancy Dodge Collection of Nonconformist Art from the Soviet Union, the Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers. Through Monday, August 31. www.zimmerlimuseum.rutgers.edu

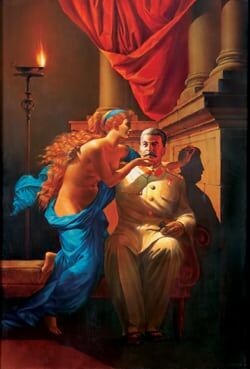

#b#Through the Looking Glass#/b# is the first thematic exhibition at the Zimmerli to chart the development of hyperrealism and photorealism in the Soviet Union during the late 1970s and 1980s. These artists challenged the hegemonic perception of reality, the heroic and idealized subjects that characterized Socialist Realism. They sought a new way to convey their reality and to dismiss the Soviet rhetoric. Exploring various themes and media, the artists developed a representation of Soviet life that reflected their surrounding urban and social environments through documentary and metaphysical lenses.

Through the Looking Glass also opens a dialogue among artists from several Soviet Republics, including Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Ukraine, and Russia. The works on view illustrate that Soviet hyperrealism was a complex and multifaceted method that arose and developed in relation to the artists’ regional and creative backgrounds. In addition, the exhibition spotlights women who pursued art careers despite the difficulties they faced in the male-dominated Soviet art scene.

“The general impulse that moved the artists’ stylistic approach was dissatisfaction with the traditional picturesqueness that defines Socialist Realism,” says Cristina Morandi, a Dodge Fellow at the Zimmerli and Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Art History at Rutgers, who organized the exhibition. “The title refers to Lewis Carroll’s book because it plays with the concept of perception. Like the protagonist Alice — who steps through a mirror in her house — these artists discovered an alternative world: a reflected, specular version of the ‘official’ reality. They dismissed the idealized world that Socialist Realist propaganda presented by showing, instead, what were considered trivial subjects and banal situations. In expanding the definition of ‘realism,’ the artists also challenged the authorized vision of Soviet reality by emphasizing the role of the artist as creator.”

Hyperrealist artists found inspiration in Photorealism, which developed in the United States and Europe during the late 1960s and 1970s. It was introduced to audiences in the Soviet Union in 1975 by Armand Hammer when he loaned work from his personal collection for the Moscow exhibition of Contemporary American Art. The un-idealized representations of reality — especially those by Chuck Close, Richard Estes, and Andy Warhol — encouraged Soviet artists to apply new methods of translating their reactions to their environments into art.

In the 1980s, hyperrealism became a direct resonator of artists’ personal lives. Many focused on their routine activities, as well as those of the people around them, carefully constructing images intended as a critique of Soviet myths. Their subjects were not heroic laborers, or the grandeur of newly built urban factories and apartment blocks, but scenes of bleak city outskirts and mundane personal activities. They captured the undesirable aspects of the life in Soviet society, exposing what was hidden behind the facade of prosperity portrayed in officially sanctioned artwork.

A selection of drawings and works on paper demonstrate their mastery of conveying even small detail. The subjects they embraced varied to show the diverse facets of daily life: street situations by Sergei Geta, urban youth by Alex Kutt, portraits combined with abstract elements by Marje Uksine. Printmaker Kaisa Puustak became recognized for her renderings of skyscrapers and railways, which often take on the appearance of photographs.

A pairing of 1960s Baltic photography with paintings from the 1980s creates a visual dialogue between the two eras. Photographers — notably Zenta Dzividzinska and Aleksandras Macijauskas — elevated ordinary existence to an aesthetic experience with such innovative techniques as cropping boundaries, adopting unusual points of view, and magnifying details. The influence is apparent in Semyon Faibisovich’s Suburbs (1984) from his “City Bus” series. The painting captures aspects of his own experiences living in a gloomy suburb of Moscow, emphasizing crowded public spaces and revealing the psychological inner worlds of fellow citizens. Here, his subjects are represented as reflections in the vehicle’s multiple windows and mirrors. The figures overlap, making it difficult to distinguish exactly where one ends and another begins; yet, they do not interact, they are isolated. They become shadows of human existence enmeshed in their surroundings; allegories of the poor quality of life that characterized the final years of the Soviet Union.

“Though these works were created more than three decades ago, the sense of alienation, disillusion, and confusion implied by many of the artists remains relevant in today’s worldwide political and economic climate,” noted Marti Mayo, the Zimmerli’s interim director. “It also provides a unique perspective for audiences — a realistic look at what life was like for a society that was veiled from the majority of Americans and Europeans. Younger audience members will gain a better sense of the change in relations between the United States and the Soviet Union, a change that occurred within the last generation and that has long lasting effects.”

Through the Looking Glass: Hyperrealism in the Soviet Union, the Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers. Through Sunday, October 11. www.zimmerlimuseum.rutgers.edu.