You might not think of yourself as a geologist. But if you’ve ever wended around the boulders in Community Park North and wondered how they got there, or walked along the Delaware and Raritan Canal and wondered why it was one of the most profitable canals in the world during the 1800s, you just might be harboring an inner geologist eager for answers.

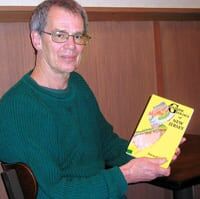

That wondering might be satisfied when Lawrence-based geologist David P. Harper presents the free program “Roadside Geology of New Jersey” at the D&R Greenway’s Johnson Education Center on Preservation Place in Princeton, on Thursday, February 6, at 6:30 p.m.

“For New Jersey geology — unless you could lay hold of a geologist — it is difficult to understand what you are seeing,” Harper says.

Harper hopes that attendees and readers of his book by the same name will learn about the geology they drive past and walk across every day and feel more grounded in their surroundings.

To help, Harper will use photos, illustrations, actual specimens, and 13 road guides showing landforms that can be seen from car windows, at parks, and on hiking trails.

Three major areas will be covered: the Newark basin, also known as Piedmont; the northern areas of the state, including the Valley and Ridge, and the Highlands; and the Coastal Plain, including the Pinelands, beaches, and marshes.

Although there is a wealth of material on the Internet and elsewhere, there is no easy way to sort it out without a guide like Harper.

“Rocky Hill has a different feel depending on whether you see it as just a hill littered with black rocks or as one outcropping of a single immense layer, a sill of igneous rock injected thousands of feet below the surface and now exposed along a 70-mile arc from New York and northeastern New Jersey, through central New Jersey — including Rocky Hill, the Pennington, Baldpate, and Sourland mountains — and on into the Solebury and Jericho mountains of Pennsylvania,” says Harper.

New Brunswick and Trenton are East Coast fall line cities, established at the head of navigation where boats had to be unloaded at Trenton, he says. “The fall line is just behind the capital building [easily seen from the Calhoun Street Bridge] where the Delaware carved down through coastal plain sediments to much older, solid rock at Trenton Falls. Before steam and electricity, many of Trenton’s industries were run by water power from the six-mile-long Trenton Water Power millrace, which carried water from Scudders Falls to about 15 feet above the river at Trenton.”

And near New Brunswick, the Raritan channel south of Bound Brook is much more recent than the Delaware at Trenton. “Before the Wisconsinan glaciers reached their maximum 20,000 years ago, the Raritan flowed eastward from Bound Brook towards Rahway. At their maximum, the glaciers blocked the old valley and sent the water southeastward to where the river now runs. The older valley lies beneath the terminal moraine built by the glaciers.

“When the Delaware and Raritan Canal was dug in the 1820s, it was designed to head into Bordentown, not Trenton. The Delaware and Raritan became one of the world’s most profitable canals not because of traffic between cities, but because it carried Pennsylvania coal to New York,” Harper says.

Harper has been interested in geology since he was a child living in the suburbs of Chicago. When he was about 12 someone gave him an antique U.S. Geological Survey report on the history of the Great Lakes. “The colored maps were beautiful, and I thought that unraveling the complex sequence of lakes through the melting back of the ice was the greatest thing since buttered toast,” Harper says.

Harper’s parents never pushed him to excel, he says, but when he found his way into geology, they encouraged him to pursue his dreams.

“Both of my parents had international reputations, my mother as a judo instructor and promoter of women’s judo; my father as a researcher in cancer and nuclear medicine.” Harper recalls how his mother supported his interests by dropping him off at geology lectures and introducing him to Chicago’s rock and mineral collecting community.

Harper studied at the University of Wisconsin, and later at Rutgers as a graduate student. He began working for the Department of Environmental Protection’s New Jersey Geological Survey in the early 1970s.

“New Jersey had been included in the 19th-century mapping of glacial deposits, but no one had looked seriously and statewide at our glacial geology since it was completed in the in early 20th century,” Harper says. “The state’s glacial geology was overdue for a new look. We now had air photos, better topographic maps, thousands of drilling logs, and a host of other tools the earlier geologists didn’t have. This is where I became respectable as a geologist.

“In the 1980s the Geological Survey began remapping all of New Jersey’s geology: glacial, bedrock, and non-glacial sediment above bedrock. We hired six fresh, young geologists, and I took a back seat as editor, making sure maps and reports were ready for publication and the printing process.” Working on glacial deposits has been one of his most satisfying experiences in geology, Harper says.

After 20 years with the Geological Survey, Harper switched gears to work for DEP’s New Jersey Site Remediation Program, focusing on gasoline-related contamination. “It was a real gift to be able to say ‘I work on cleaning up soil and water contamination [originating] at gas stations,’ and have people know exactly what I was doing and why. Later still, I continued to work on gasoline contamination as a private-sector consultant.”

In spite of his work as a professional geologist, his tenure as president of the Geological Association of NJ (GANJ), and his role as adjunct teacher at Rider University, Mercer County Community College, and New Jersey City University, Harper says he wasn’t fully prepared to write the book until he began his own personal research and became immersed in the writing process. At the encouragement of GANJ, he created a series of geology themed calendars from 2007 to 2011.

Although the calendar dates are not current, the information and photos are relevant today and can be downloaded for free at ganj.org.

“Creating the calendars gave me a chance to get out and explore, talk to people, and collect photos,” Harper says, noting that the process helped prepare him for the rigors of writing the book.

You can form an impression of a place based on something you read, Harper says, but when you actually go there, your impression could change. There may be new outcroppings since the author had written about the place. Or maybe he had focused on what mattered to him, noticing some things but not others. When you go out into the field, you need to keep an open mind about what you might see. In spite of his professional experience, he’s still learning, Harper says.

“New Jersey has a lot of interesting geology, and it’s out there for you to see.”

Roadside Geology of New Jersey, D&R Greenway’s Johnson Education Center, Preservation Place, Princeton. Presentation by David P. Harper. Thursday, February 6, 6:30 to 8 p.m. Free, but donations welcome. Reservations suggested. rsvp@drgreenway.org or 609-924-4646.